Fritz Haller in Space

Return to Articles

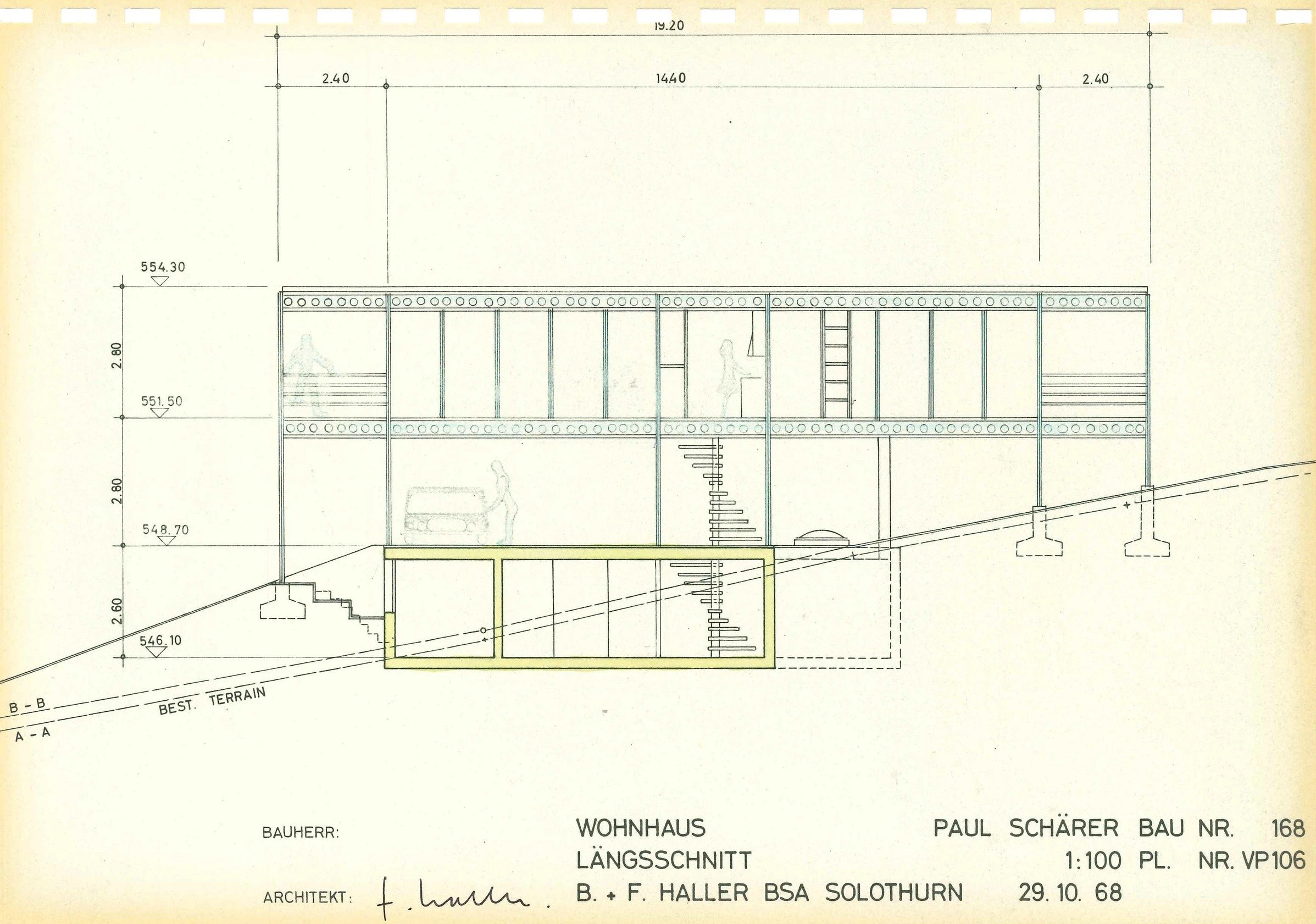

Fritz Haller, Buchli (1968). Section, north-south

The Swiss architect famous for designing the iconic USM Haller modular furniture system was, less famously, a spaceman. In 1961, when Fritz Haller first met Paul Schaerer—the third generation of the Schaerer family to helm the USM furniture company—Haller was a young, homegrown architect with only a handful of school buildings to his credit. But he was quickly emerging as a leader among a close-knit cadre working to revive a dream that had been kindled in the years before World War II—the unity of architecture and industry.

Born in 1924, Haller came of age during the gravest period of upheaval in modern history. While the world tore itself apart between 1941 and 1945, Haller’s formative years were spent in the security of neutral Helvetia. He studied architecture, learning from the graying modernists at ETH Zurich (also known as the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), and later, he apprenticed in the architectural firm of his father, Bruno Haller. It was only three years after the war’s end, in 1948, that the twenty-four-year-old Haller saw the destruction of the war firsthand. In Rotterdam, a city in ruins from German Luftwaffe bombs, he spent the next year working in the office of Willem van Tijen, a card-carrying member of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), and at the time, a designer kept busy by the urgent reconstruction of the city. Haller learned much from van Tijen; most of all, he gained a deep understanding of what led the lofty idealism of the prewar architectural avant-garde to give way to ruthless pragmatism—the only reasonable position for architects in a city that had been all but annihilated in a single night of bombing.

Thirteen years after he first set foot in Rotterdam, Haller waited in his small office in Solothurn, Switzerland, a city that had been built over an ancient Roman castrum, or fortress, laid out, as they were throughout the empire, on a rectangular grid. Haller was meeting Schaerer—the man who would make his career. Just thirty-seven years old, Haller was a young architect by any measure, but Schaerer was younger—just twenty-eight years old—and ambitious. Trained as an engineer, Schaerer immediately recognized the potential in Haller’s systematic approach. The stars seemed to align: Haller’s expertise, combined with Schaerer’s vision for modernizing his family’s nineteenth-century company, set both men on a course that led further than either had ever imagined.

The USM factory in Münsingen, Switzerland, employed the Haller MAXI system of modular construction. It has been expanded three times since 1965. Photo courtesy of USM U. Schärer Söhne AG.

Within a decade, Haller’s collaboration with Schaerer saw the architect’s dream of a world made rational begin to materialize. Their first project, a new factory for USM in Münsingen—where it remains today—was completed in 1963. A glass-walled office pavilion followed two years later. The standardized, steel-frame construction techniques Haller devised for both of these projects, which were published to great acclaim, were subsequently brought to market as the MINI, MIDI, and MAXI lines of prefabricated building systems. The underlying square grid of each was optimized for a specific structural scale, from the intimate spaces of a home or office to the brawny spans of an industrial warehouse; however, all three systems shared the ability to be infinitely extended and reconfigured. Meanwhile, the modular steel-tube furniture that Haller and Schaerer initially intended solely to outfit USM new headquarters proved popular, and these too were soon industrially produced en masse: the first six hundred units were ordered by the Rothschild Bank in Paris. When USM Haller hit the commercial market in 1969, the Swiss company was fabricating modular furniture within modular buildings, their respective grids neatly nesting, one within the other, as if modernist matryoshka dolls. To the architect’s eyes, it seemed that more and more of the world was subtended by a previously unnoticed Cartesian grid, an irreducible stratum of rationality. The only space left unmarked, it seemed, was up.

Haller’s collaboration with Schaerer and USM ran parallel to the most eventful years of the space race: Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to orbit the earth in 1961, and eight years later, in 1969, two Americans, Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, trod upon the lunar surface. A pervasive spirit of technological optimism built with each new advance—undoubtedly a boon to the future-minded architect. But more decisive still was the sense that the world was quickly expanding. The war-worn avant-gardes of the past had been tethered to a terrestrial worldview while pursuing a new, “universal” modern space that always remained just out of reach, tantalizing, yet ultimately theoretical. By contrast, Haller’s generation, which captured the “Earthrise '' photograph on Christmas Eve in 1968, saw the planet from the outside for the first time in human history. Now, the world—and space itself—were universal in fact.

These same years saw Haller’s output grow rapidly, quickly ascending through telescoping scales that tended, asymptotically, toward the infinite. The range of his projects in these pivotal years is cosmic: from the miniscule ball-joints of the USM furniture system patented in 1965 to the finely-tuned elements of the prefabricated factory buildings erected in 1964 to the design of cities for an interconnected planet published in Totale Stadt: Eine Globales Modell in 1974, and finally, to the occupation of outer space. This last chapter, which was published as the Environmental Design of a Prototypical Space Colony, arrived in 1980. It had been preceded by years of intensive study and marked the logical endpoint of Haller’s decades-long trajectory: architecture refigured as pure technical system. For Haller, space was not architecture’s final frontier, as it were, but rather the ultimate test case for terrestrial building: the problems of building on Earth are not eased in space, but intensified. In orbit, the prudent management of energy, water, heat, and air—the lodestars of Haller’s architecture—is a matter of survival.

In 1962, architect Fritz Haller and USM owner Paul Schaerer developed a modular furniture system to match the modularity of the new factory. This furniture is based on a system of adaptable steel modules of panels, tubes, and ball joints.

Somewhere about halfway along the eccentric trajectory that runs from the chrome-plated brass ball-joints of the USM Haller system to the architect’s late hypothetical space capsules lies a small house in the Swiss countryside. Located on a hillside in Münsingen, Switzerland, the structure is perched above the prefabricated factory buildings where, today, a legion of robots and whirring machines manufacture Haller’s designs with mechanical precision, executing their work almost automatically. This house is another outpost of Haller’s rational world. Designed for the Schaerer family in 1968, it was only the second application of the MINI steel construction system after its first use to erect the USM company’s office pavilion. Construction was completed in 1969. The house was given the name “Buchli,” after a farm that once sat on the property.

The Buchli House, built in 1969 for the Schaerer family, employed the MINI construction system.

Photo by Simon Opladen.