Teaching Systems: Konrad Wachsmann at the University School of California Building Institute

Return to Articles

Download PDF (English)

Download PDF (Deutsch)

Machine Learning in Design Theory, the fourth issue of the ‘Schools of Departure’ journal, focuses on the topic of technology in design education beyond the Bauhaus. From cybernetics to semiotics and systems theory – in a large-scale wave of cybernetization in the second half of the 20th century, the belief in the triad of knowledge, technology and progress once again appears unbroken in universities and research institutions. Thus, the relationship between design education and technology in the 20th and 21st centuries is reflected in the different ideas that designers and architects have developed about machines – and how they position themselves in relation to them.

Edited by Regina Bittner, Katja Klaus und Philipp Sack

Contributors: Anna Bokov, Georg Vrachliotis, John R. Blakinger, Ezgi Isbilen, Phillip Denny, Gui Bonsiepe, Susan Snodgrass, Vikram Bhatt and Leonie Bunte, Maria Göransdotter, Aldje van Meer

Teaching Systems: Konrad Wachsmann at the University School of California Building Institute

Konrad Wachsmann's designs for prefabricated building systems are well-known, but his pedagogical career has been somewhat overlooked. This fact is curious if only because Wachsmann was ultimately a more prolific teacher than builder, and this parallel activity extended almost continuously from his appointment to the faculty of the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1950 until his death in Los Angeles in 1980.

Indeed, Wachsmann’s best-known architectural projects, such as the demountable hangar system for the U.S. Air Force, came about only by virtue of his academic work: the hangar was developed and executed with the help of a team of graduate students in the architect’s research group in Chicago. In light of Wachsmann’s passion for systematicity, it seems appropriate to ask the question directly: what is the pedagogy of systems? If the aim of the architect’s building systems was to provide a construction technique with universal applications, that is, systems appropriate to any use and outcome, then how could this ideal be taught in a manner that was similarly open-ended?Wachsmann’s answer was, of course, systematic. Beginning in the 1950s, the architect developed a set of instructional techniques, a ‘teaching system’, that enacted a strict protocol for classroom activity but which conspicuously did not define content or curriculum. Every workshop would proceed thus: students, ideally 21 of them, work collaboratively on a design problem. The group divides the problem into seven sub-problems, which are then addressed by teams of three students each. The teams then share their findings with one another in a series of structured conversations and build up the solution collaboratively. These techniques were the script for the Salzburg Summer Academy workshops held in the 1950s, in which students (one year including a young Hans Hollein), worked collaboratively on a design project. The 1956 academy designed and constructed a chalet for Sigfried Giedion in Amden, Switzerland.Wachsmann’s last major project developed this systematic pedagogical format as the basis of a permanent research centre in Los Angeles. This organisation, known as the Building Institute at the University of Southern California (USC), represents a significantly more complex application of the teamwork concept, integrating purpose-built spaces, a unique organisational structure and cybernetic principles of information control toward the production of research. The history of this organisation demonstrates how the production of a pedagogical system was aligned with the project of resituating the architect as an agent working to affect larger systems and structures beyond the studio: university, industry, and as Wachsmann wrote in the Building Institute’s founding documents, no less than ‘The Society of Man’ itself.

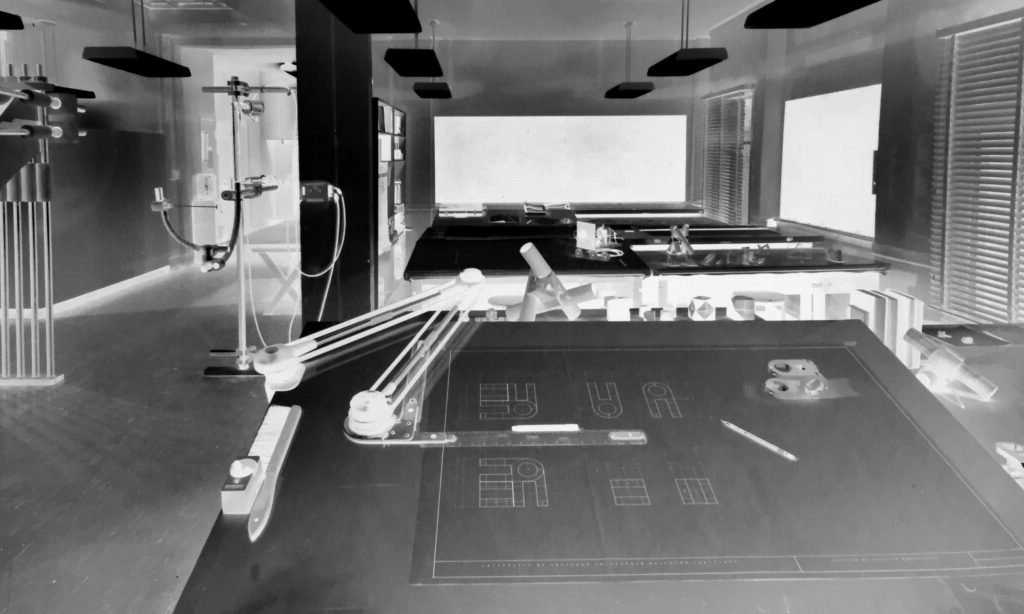

Main workspace at the USC Building Institute, circa 1970. Courtesy of John Bollinger.

Planning for the Building Institute at USC began in Italy in 1963. Crombie Taylor, a former colleague of Wachsmann’s at the Institute of Design in Chicago, had been appointed associate dean of the School of Architecture in Los Angeles. Working in Genoa on what would ultimately be an ill-fated project to redesign the city’s port district, Wachsmann went to Los Angeles without hesitation. At USC, Taylor handed down a directive to reconceive the school’s graduate programmes, and accordingly, Wachsmann undertook a year-long study for the potential curriculum. This preliminary work was funded by the Graham Foundation and took the form of a series of diagrams published in 1964. Wachsmann’s proposed answer was the Building Institute, a research centre that would allow graduate students to work collaboratively on funded research under the direction of the faculty, in pursuit of the degree Master of Building Science.In some ways, the Institute replicated a model for conducting sponsored research that Wachsmann had developed at the Institute of Design a decade earlier. In Chicago, a government contract to produce a prefabricated system for aircraft hangars had allowed Wachsmann and several students to develop tubular steel space frame structures over the course of five years. The Institute would also be premised on sponsored research, but finding sponsors was a problem at first. Although Wachsmann had been appointed in 1964, it wasn’t until three years later, in 1967, that the Institute received its first sponsored research grant. In the meanwhile, the Institute pursued technical research in the context of Wachsmann’s architecture practice, which was then engaged in the design of a city hall for California City. Although this project supported the Institute and its investigators, it represented just one small facet of the organisation’s stated mission as a ‘center of study, research, development, and information related to all aspects of industrialization and its impact upon planning and architecture’.[1]The founder of the Building Institute imagined that it would be the nucleus of a continuously expanding network of allied disciplines spanning the sciences and the arts. In a memo to the university president, Wachsmann outlined six basic components of the program: basic research, applied research, student training, teacher training, a doctoral program in building science and an information centre. The Institute would act as a medium for leveraging the combined expertise of the university toward the transformation of the built environment. The scope and shape of the organisation’s mission had been defined in the series of diagrams that Wachsmann drafted soon after arriving in California, but it was the design of the Institute’s space that would be tasked with translating these concepts into physical space.

Buckminster Fuller and Konrad Wachsmann in conversation in front of an image of the California City project. Taken at the opening of the exhibition “Konrad Wachsmann: 50 Years of Life and Work Toward Industrialization of Building,” at the USC Fisher Gallery in 1971. Photograph: Allan Dean Walker. Crombie Taylor Papers, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago. Digital File # 201005_200128-001

The Institute sought to establish a pedagogical system whose parallel functions as didactic environment and as experimental laboratory would be coproductive.

As campus protests against the Vietnam War reached a boiling point at the end of the 1960s, Wachsmann, who had worked for the U.S. military during and after World War II, established the Institute on the edge of the USC campus in what was formerly the armory of the 160th Army Infantry Regiment. The building was well-suited to the Institute’s needs: the vast drill hall at the centre of the building gave researchers ample space to stage prototypes and exhibitions, and wings of offices on either side of the hall were renovated to accommodate the Institute’s vision of an ‘interdisciplinary research organism.’Successive drafts of the Institute’s floorplan incrementally adapted the building to the structural clarity of the institutional diagram. Each space was developed in light of the essential activities of the Institute. For instance, the ‘laboratory’ would be a machine shop for producing research prototypes, and the ‘information centre’ would provide a hard-wired connection to USC’s mainframe computer and “include every possible medium of communication”, according to its creator.

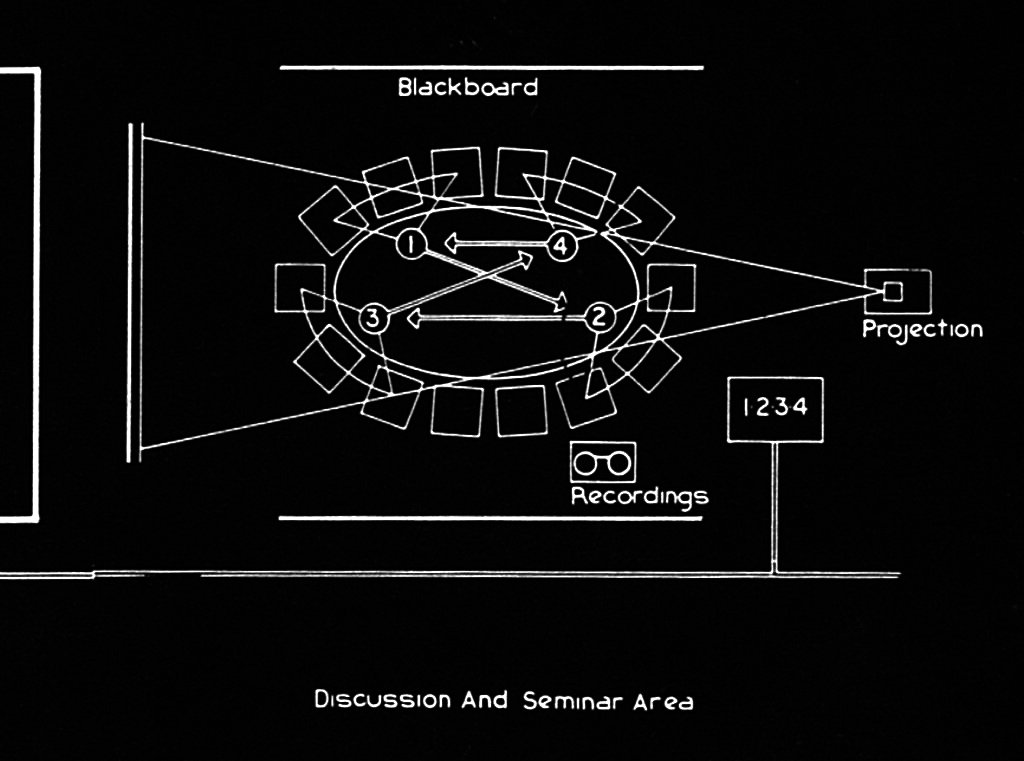

Drawing of an ideal conference room set-up and seating arrangement for a “superteam” of four, three-person groups working collaboratively on a task. Each group would cycle through smaller tasks throughout the course of a larger project, thus ensuring that each problem is addressed by the complete range of expertise and creative viewpoints in any given team. Courtesy of John Bollinger.

But the conference room was the true heart of the Institute. Following the seminar protocols that Wachsmann had invented in the 1950s, structured discussions around the oblong table would be recorded and entered into the Institute’s database for future reference. The ability to capture information as soon as it was broadcast allowed the Institute to close the feedback loop back upon itself, recapturing information as an asset to future research. The social functioning of the room was strictly planned in Wachsmann’s curriculum charts, which include a seating plan for optimum discussion between teams. Like the Building Institute’s other spaces, the conference room was designed to facilitate the production and transmission of information. Whether taking the form of models, drawings, lectures, photographs, films or prototypes, the Institute’s essential preoccupation was the circulation of information.Maximizing the number of productive nodes enmeshed in the network was one strategy for raising the status of the research. Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and design theorist Horst Rittel both made visits to the Institute, and Richard Buckminster Fuller frequently stopped by on visits to Los Angeles during the development of the ‘World Game’ in the 1960s. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe also visited once, and by one student’s recollection, the ailing master had to be lifted upstairs to the Institute by means of a forklift in the armory hall. Fritz Haller, too, was a collaborator of the Institute from 1966 to 1971, developing grid structures that anticipated his later commercial designs for building systems. But the only project known to have been realized by the Institute was the Location Orientation Manipulator, the L.O.M., a robotic arm designed by two doctoral students, John Bollinger and Xavier Mendoza. The purpose of the device was to study the ‘kinematics of prefabricated building’, that is, the manipulation of objects in space. It was funded by a three-year grant from the Weyerhaeuser Lumber Corporation, and it marked the Institute’s definitive move into ‘basic research’. Defined by Vannevar Bush in 1945 as an inquiry that “is performed without thought of practical ends”, this type of work produced not solutions but “general knowledge and an understanding of nature and its laws”.[2]Whereas the earlier study of structural systems for the California City City Hall was developed in the context an architectural project, the L.O.M. device had no such immediate applications. Rather, the creation of this instrument for studying the problems of building assembly was itself the research agenda.Indeed, outside of the Institute, the L.O.M. had no useful purpose. The device was not sophisticated enough to be taken up by the building industry, and thus its sponsors could not exploit it for production. Eventually, the impressive device was disassembled, boxed up, and lost. But between 1967 and 1971, the L.O.M. proved immeasurably useful to the Institute’s protagonists. For Wachsmann, the device was the Institute’s raison d’être, a high-profile and big-budget project that justified his organisation’s continued existence. For the sponsors, it was an opportunity to ally their corporation with the cutting-edge of building science research at a prestigious university. For the graduate students Bollinger and Mendoza, the device was an expedient to their doctoral degrees. Common to all of these purposes, however, was the device’s ability to yield alluring images.

The L.O.M. project was completed in 1971, when doctoral students John Bollinger and Xavier Mendoza defended their joint dissertation. Courtesy of John Bollinger.

Whether appearing in photographs in Weyerhaeuser’s publicity materials or in Bollinger and Mendoza’s joint dissertation or in Wachsmann’s slide lectures, the L.O.M. was an object of distinguished aesthetic presence that rather resembled László Moholy-Nagy’s ‘Light-Space Modulator’ more than an experimental apparatus. As an object of considerable aesthetic quality but little value to either further research or applied use, the L.O.M. can be said to embody the Building Institute’s central paradox: as Wachsmann’s research agenda became more theoretically speculative, the value of his research to sponsors, whether government or corporate, diminished in kind.After completion of the L.O.M. project in 1971, the Institute would constantly struggle to justify its own existence as a venue for experimental work on building science and technology. The Institute had placed itself at odds with the prevailing dynamics of the Cold War research economy. First, by avoiding applied research, the Institute could not offer compelling arguments that would entice corporations to sponsor new projects. Second, Wachsmann’s ‘hypothesis-free’ ethos of experiment alienated him with respect to public sources of funding for scientific research. In response to questions about what could be gained by undertaking projects like the L.O.M., Wachsmann replied, “… my answer always was, that I did not know. But this was the same answer I would always give when I worked on any task. If I would know the solution or the purpose, I would not start at all.”

The Building Institute was shuttered for lack of funding in 1974, but not before Wachsmann had developed a teaching system that sought to standardise the production of knowledge and built a school to implement it. In the context of the architect’s lifelong engagement with industrialisation, the Institute represents the architect’s most sophisticated proposal for architecture’s alignment with science and industry. That this confluence would take place on the grounds of a school resonated both with the programme of the Bauhaus and the emerging neoliberal transformation of the university, what President Dwight D. Eisenhower called in 1961 the ‘military-industrial-academic complex’.

Drawings of L.O.M. components on a drawing board in the Building Institute workspace circa 1970. A partial prototype of the device can be seen near the corridor. Courtesy of John Bollinger.

The case of the Building Institute is exceptional with respect to other organisations for building science in its time. It is unusual in that it was simultaneously unable to accede to the demands of the research economy, and yet it nevertheless fashioned itself after the model of scientific research laboratories in the university. Rather, the Institute sought to establish a pedagogical system whose parallel functions as didactic environment and as experimental laboratory would be coproductive. Whether in the Institute conference room or in the laboratory, new information would be produced, captured, and capitalized upon as the product of sponsored research. Students would train to become participants in this circular production of valuable knowledge, and in the process, their academic labour became the Institute’s product.But Wachsmann’s unerring faith in the value of design did not match the evaluative calculus of his would-be sponsors. Still, the architect’s systematic transformation of pedagogical activity into an economically productive process pointed in the direction that building science laboratories, and academic science in general, would take after the 1970s. As was true in the case of the Building Institute and other university laboratories, physical space gathered the resources of the university— material and personnel— for the purpose of producing saleable research. In this respect, the Institute was established precisely on the historical fulcrum which saw a pivot from industrial forms of production to the post-industrial economy. Whereas Wachsmann’s early-career efforts to develop prefabricated building systems sought to subsume architecture within industry, the Building Institute thus attempted to reconstitute architecture itself as a technological product produced by scientific labour.

Notes

This essay was first published in: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (ed.). The Art of Joining. Designing the Universal Connector (Bauhaus Taschenbuch; 23) Leipzig: Spector 2019, pp. 66-83.

1 Memo to Dr. Milton C. Kloetzel. “Proposal to authorize the creation of a Building Institute,” May 22, 1968, in: Crombie Taylor Papers, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of the Art Institute of Chicago, Box 5, Series 19, Memos, Wachsmann USC.

2 Vannevar Bush was director of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II. Vannevar Bush. Science, the endless frontier, 1945.

3 Konrad Wachsmann, The Future is everything; from an unpublished autobiographical manuscript., 1901, Timbridge 2001, viewed at the Academy of Arts, Berlin; Konrad Wachsmann Archive, Wachsmann 2128.